|

| Omar Al-Ubaydli |

By Omar Al-Ubaydli

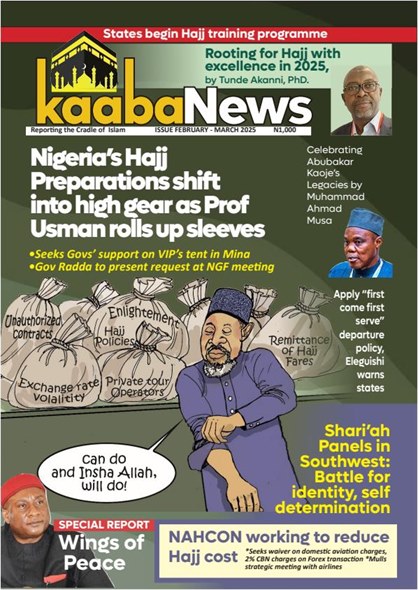

Recently, Saudi Arabia loosened travel restrictions on women. While reforms relating to personal rights, including this measure and allowing women to drive, tend to dominate the headlines, they also fall under the Saudi government’s broader effort to increase female labor market participation. A look at the academic literature on the determinants of female labor supply confirms that the Saudi government is being methodical and meticulous in its reforms.

Contrary to popular belief, Saudi Arabia has actually had some policies that promote female labor force participation prior to the more recent reforms. Working hours in the public sector – Saudi Arabia’s largest employer – are relatively short and well-aligned with the school day, suiting women with children. Moreover, although Saudi maternity leave is relatively short by international standards, the typical paid leave in the public sector (36 days plus around 15 days of public holidays annually) far exceeds even the most generous leave policies recorded by the OECD.

Furthermore, Saudi Arabian citizens can easily hire migrant workers as live-in domestic helpers to assist with child-rearing and all other domestic chores for less than $400 per month. In contrast, in several Western economies, couples have to spend over 30 percent of their income on childcare alone.

Yet despite these policies, a combination of legal, economic, and cultural barriers have yielded a female labor force participation rate of only approximately 18 percent in 2017. Previously, women were held back by needing the approval of their male guardians to work, being unable to drive, and the absence of women in leadership positions. The last of these is still a factor, while social disapproval of women working also affects female labor force participation.

In the last five years especially, the government has taken substantive steps to get women into the workforce. The variety and depth of the reforms is remarkable, and indicates a methodical approach to reversing one of the lowest rates in the world.

In the last five years especially, the government has taken substantive steps to get women into the workforce. The variety and depth of the reforms is remarkable, and indicates a methodical approach to reversing one of the lowest rates in the world.

For example, in early 2018, the Saudi government announced plans to establish 233 new childcare centers in the Kingdom for those unable or unwilling to rely on grandparents or domestic helpers as their primary source childcare. The government also offers over $200 a month of childcare subsidies to working women. Moreover, in response to women valuing worktime flexibility, labor laws are supportive of part-time work, which includes social security, overtime, annual leave, and sick leave.

The ban on women driving has been removed, eliminating a massive barrier to women working. And it is likely that the aforementioned relaxation of travel restrictions is the precursor to the elimination of the male guardianship system. Moreover, changes to labor laws to and to the guardianship system during the last five years have eliminated the legal requirement for women to acquire their male guardian’s approval to work, allowing women to make unilateral labor force participation decisions.

The government has also applied Saudization quotas – requiring businesses to employ a quota of Saudi citizens – much more stringently than before, including the elimination of migrant workers in large sectors such as telecommunications. This creates job opportunities for Saudi women, especially in the sectors that are relatively popular with women, such as the retail sector. Notably, the increasing restrictions have not been applied to domestic helpers, suggesting the government realizes that they contribute positively to female labor force participation among Saudi women.

The practice of restricting certain positions to men, such as working in the Ministry of Interior, has been scaled back, and this legal reform has been complemented by appointing women to leadership positions historically reserved for men on cultural grounds. One of the most salient examples is the appointment of Princess Reema bint Bandar al-Saud to the high profile post of Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the US. And more recently, the Saudization policies have also been modified to include positive discrimination elements: Private companies will be fined $4,000 if they fail to employ two women in each shift.

The practice of restricting certain positions to men, such as working in the Ministry of Interior, has been scaled back, and this legal reform has been complemented by appointing women to leadership positions historically reserved for men on cultural grounds. One of the most salient examples is the appointment of Princess Reema bint Bandar al-Saud to the high profile post of Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the US. And more recently, the Saudization policies have also been modified to include positive discrimination elements: Private companies will be fined $4,000 if they fail to employ two women in each shift.

The government has also tried to effect top-down changes in societal attitudes. Last year, the Crown Prince himself stated that Saudi women do not need to wear traditional black abayas or head scarves, while at the same time heavily curtailing the religious police’s power. It has also been vigorous in passing and enforcing laws that protect women from sexual harassment, since the adverse physical and psychological consequences of harassment are known to be barriers for female labor force participation globally.

What explains the government’s apparent urgency? Beyond political considerations relating to women’s rights, there are important economic factors that play a role.

What explains the government’s apparent urgency? Beyond political considerations relating to women’s rights, there are important economic factors that play a role.

First, women are just as talented and productive as men, and so it is costly to deny oneself access to their talents. Whether we are speaking of ambassadors, CEOs, or police, artificially restricting the talent pool to men necessarily implies lower quality.

Second, when women earn an income, it raises household income and gross consumption, giving the economy a boost. And if that income would have otherwise gone to a migrant worker who would remit it home rather than spending it in Saudi Arabia, this is a double win.

Finally, female employment often directly leads to a decrease in the rate of population growth. Population growth creates pressure on public finances, and increases the need for job creation, both of which are challenges faced by Saudi Arabia at present, and so the government may see greater female labor force participation as a partial antidote.

The remarkable pace and breadth of the reforms has yielded rapid improvements in female labor force participation, going from 18 percent in 2017 to 23 percent in 2018 according to World Bank statistics. But this figure is still much lower than the OECD average of 59 percent. Women continue to face barriers to work, and even the most aggressive top-down initiatives have to be complemented by grassroots efforts at the family and school level to ensure lasting changes in cultural attitudes. Talking to women directly and involving them in the decision-making process will be critical to realizing additional gains in the coming years.

- Advertisement -